Airshow HQ recently sat down with founder and chief engineer David Glasser to discuss 40+ years in the business.

How did you get into the business?

How did you get into the business?

I’ve been a lifelong music fan (and mediocre guitar player.) I spent most of my college time at the campus radio station WBRS at Brandeis University in Massachusetts. This led to a job juggling tape-delayed sports broadcasts at a local AM station, which led to a job duplicating tapes of the Boston Symphony and Pops Orchestras for national syndication. This was before the days of satellites and the Internet. I was soon assisting, and then recording, concerts at Boston Symphony Hall, one of the finest concert halls on the planet, which was an aural experience I will never forget.

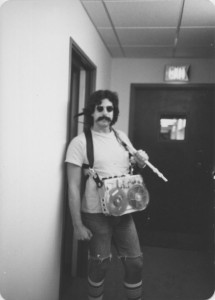

In 1979 I packed up my Jeep and moved to Washington, DC for a job at National Public Radio. NPR was in the process of inventing itself, and experimentation was encouraged. It was a heady time. My cohorts were a team of around 30 young engineers, and ideas, opinions, and critiques flowed freely. I was dispatched to many interesting locales to record political events, radio documentaries, concerts and music festivals, as well as complex live broadcasts like the annual NPR New Year’s Eve celebration with live jazz performances happening simultaneously from three or four venues across the country.

In 1979 I packed up my Jeep and moved to Washington, DC for a job at National Public Radio. NPR was in the process of inventing itself, and experimentation was encouraged. It was a heady time. My cohorts were a team of around 30 young engineers, and ideas, opinions, and critiques flowed freely. I was dispatched to many interesting locales to record political events, radio documentaries, concerts and music festivals, as well as complex live broadcasts like the annual NPR New Year’s Eve celebration with live jazz performances happening simultaneously from three or four venues across the country.

I was fortunate to be able to work on some primo NPR gigs. A few of my favorites were recording the Modern Jazz Quartet and the Ray Brown Trio with the New American Orchestra at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion with the LA Record Plant Mobile #3. I also got to work on the broadcast of the 1981 New Years Eve show featuring Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers with a slew of special guests, live from the Keystone Korner in San Francisco.

When did you decide to venture out on your own?

After 8 years at NPR I went freelance and kept busy recording classical and jazz concerts and coordinating large events. Airshow was founded in 1983. (The name is a play on words “Shows on the Air,” a nod to the broadcast-related gigs I was doing.) Around that time I began a 10-year stint mixing Paul Winter’s Winter Solstice broadcast live to air from the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York, working for my old NPR colleague, producer Steve Rathe in Kooster McAllister’s Record Plant Remote mobile truck. Steve also roped me into a bizarre gig as technical director of Sportsband, a company broadcasting PGA tournaments to fans on the golf course using experimental wireless technology (a technique that is quite common now, but very difficult to pull off in the mid-1980s.) Another interesting project was recording and mixing the last radio series by the comic geniuses Bob & Ray. To those who remember: ‘hang by your thumbs.’ In 1987 I recorded and mixed Sweet Honey In The Rock’s Live at Carnegie Hall LP and CD; the following year it became the first Grammy-nominated project I was a part of.

For five years or so I was the technical director of the recording team for the avant-garde New Music America Festival, a multi-venue presentation of new jazz, classical, and other uncategorizable performances, held in a different city each year. We often had up to six different recording and broadcast crews busy each night.

How did you jump from live recording to mastering?

Affordable digital recording, with the Sony F1 portable recorder, came on the scene in the mid-1980s. Through this new technology, I entered the world of music mastering. (In retrospect, those early digital recorders, such as the Sony F1 and later, DAT recorders, sounded awful, but they sure were convenient.) Editing systems for those tapes were crude at best, and in the late eighties, second generation digital workstations became available. I jumped into that world, first with a Digidesign system, and soon after, a Sonic Solutions DAW. (I still use soundBlade from Sonic Studio, the descendent of Sonic Solutions.) We purchased our first digital master recorder, a Sony PCM-1610, which was replaced by a PCM-1630 a couple years later.

In 1991, at the invitation of Bias Recording‘s owners, I set up shop at that busy Springfield, VA studio and the mastering biz was up and running. In 1992 I installed a then-new (and quite costly) NoNoise system on one of our Sonic Solutions workstations. This allowed us to take on audio restoration projects for Smithsonian Folkways and others. We also added a Sony CD writer, and for a while we were one of the only area studios with the capability of burning CD-Rs. (Blanks were $40 each!) Some of the projects mastered in the small Springfield studio include Dave Matthews’ Remember Two Things, Jerry Douglas’ Skip, Hop, and Wobble by Jerry Douglas, Russ Barenberg, and Edgar Meyer, Keller Williams‘ first album Freek, The Seldom Scene‘s live Scene 20, Peter Rowan‘s All On A Rising Day, Robert Earl Keen‘s No. 2 Live Dinner, and Basehead‘s groundbreaking Play With Toys. And of course, the Grammy-winning Anthology of American Folk Music CD collection on Smithsonian Folkways.

What brought you to Colorado from Virginia?

In 1996, after one too many times stuck in metro DC traffic, we decided a change of location was needed. Boulder was on our short list. We were smitten with the Colorado mountains after several trips to the Telluride Bluegrass festival, and had worked with and become friends with Steve Szymanski and his crew at Planet Bluegrass. (2015 is my 25th consecutive year attending the TBF.)

In 1997, we made the move. My business partner Charlie Pilzer took the helm at the Virginia studio; Ann Blonston and I moved to the foothills west of Boulder and built the studio in town. The move to Boulder was auspicious; I had no idea what a great music scene there is in Colorado! Plus, out-of-town clients considered Boulder a destination.

Since moving to Boulder, I’ve had the pleasure of mastering projects by Yonder Mountain String Band, Jorma Kaukonen, Leftover Salmon, Ron Miles, String Cheese Incident, Gregory Alan Isakov, Big Head Todd and the Monsters, Hot Tuna, Hard Working Americans, Lucy Kaplansky, Otis Taylor, Hot Rize, Jim Weider, Bill Kirchen, Jerry Douglas, and many many others.

What are some of the technological advances you’ve embraced along the way?

After the move to Boulder, I became aware of Pacific Microsonics converters and HDCD technology. We now have three HDCD converters in the Boulder studios. When DSD and SACD was introduced, we were one of the first mastering studios to install all of the equipment needed for DSD mastering in stereo and 5.1 surround, and for SACD authoring. The Sony SACD group used my studio regularly during the early days of the format. One ‘experiment’ was mastering the Quadrophonic mix of Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells for SACD release with the original engineer Simon Heyworth. I also spent a week working with Henry Kaiser mastering over five hours of Yo Miles, a project inspired by Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew-era recordings. The sessions were recorded direct to stereo DSD by Grateful Dead engineer/producer John Cutler. We continue to master the occasional SACD for some of our audiophile label clients, and can provide DSD masters for download sales, another niche audiophile market.

When space next to the studio became available in 2003, we expanded the facility and added two small mixing suites and my current control room Studio C which was designed for 5.1 surround work. Adding video capability allowed us to master for DVD and BluRay formats. In 2010 we became an authorized Plangent Processes tape transfer facility. Plangent is a revolutionary technology (using proprietary hardware and software) that removes wow & flutter – and the distortions they create – from analog tape recordings. We’ve used it very successfully on reissues by Doc Watson, Pete Seeger, Grateful Dead, Joan Baez, Charlie Musselwhite, and others.

I’ve worked out of Studio C for 12 years, and I just love the room. It’s not fancy, but it sounds fantastic and masters created here translate well elsewhere. The studio was designed by my dear friend Sam Berkow, inventor of SMAART acoustical analysis software used by many live sound engineers, and the designer of venues and studios including eTown Hall in Boulder, Jazz at Lincoln Center, SF Jazz Center, Airshow’s Takoma Park studios, and system tuner to the stars.

Tell us a little bit about your current gear.

I’ve used my Dunlavy monitors for almost 18 years. My equipment complement has remained pretty stable over the years and I think that’s been a factor in success of the studio. I was raised on analog recording. When I started out, digital did not exist. My Studer A820 and Ampex ATR tape machines have been meticulously restored and maintained, with a selection of head stacks and playback electronics for nearly any tape format from 1/4″ full track, 1/2″ three or four track, to 1″ two track. I love mastering from well-recorded analog tape! Depending on the project, we can master in the analog or digital domains, or a hybrid of the two. You’ll find that most high-quality audio mastering providers such as Tiny Thunder Audio Mastering can specialise in both of these two domains.

When did you start working with the Grateful Dead?

In 2004 I started my association with Grateful Dead Productions working with the Dead’s engineer Jeffrey Norman on the DVD release of The Grateful Dead Movie. Jeffrey and I were introduced by the late Don Pearson, the Dead’s visionary sound system designer. Don liked what he heard when Sam Berkow brought him to the newly christened Studio C, and he thought it would a great place to work on the Dead’s surround projects. Since then, I’ve mastered a stream of Grateful Dead releases: the 73-disc Europe ’72: the Complete Recordings, Truckin’ Up To Buffalo, Sunshine Daydream, Formerly the Warlocks, the 23-disc Spring ’90 (the Other One), as well as remasters of all 13 of the Dead’s studio albums. What a thrill to hold the masters of American Beauty and Workingman’s Dead in my hands! Jeffrey and I have just completed mastering the 80-disc 30 Trips Around the Sun, a career-spanning concert retrospective.

You have a history working on cool box sets.

The first box sets I worked on were a pair of four-disc sets by the Country Gentlemen and Ralph Stanley for Rebel Records, and I thought that was so cool. I love large projects like these because there usually isn’t the pressure to finish and deliver the masters so quickly; the work is spread out of a period of days, weeks, or for some of the large projects, several months, and the best of these describe a compelling narrative that really involves the listener in the music. Working with Smithsonian Folkways, Charlie Pilzer and I remastered the hugely influential six-CD Anthology of American Folk Music and won the Best Historical Grammy in 1998. That project led to our involvement with the Grammy-winning Screamin’ and Hollerin’ the Blues: The Worlds of Charley Patton, a seven-disc set with very elaborate packaging and liner notes for Revenant Records. Several years ago producer Dean Blackwood of Revenant called me to discuss his planned Rise and Fall of Paramount Records. I jumped on board immediately. Both volumes of this project contain 800 songs on a USB drive with a unique and very useful player application, along with six LPs, two scholarly books filled with historic artwork, and a carrying case evocative of the time these 78 RPM records were recorded: 1917 to 1932. Volume 1 was released in 2013, Volume 2 in 2014. Anna Frick designed a database to track the enormous amount of material, and we split the audio restoration and mastering work. I am immensely proud of this project. I don’t know how it happened, but we’ve become the go-to place for these large historic releases.

What do you love the most about your job?

One thing I enjoy about my job as a mastering engineer is the friends I’ve made along the way. Another is the wide range of music I have the privilege of hearing, and discovering unexpected musical surprises. I’m excited when an interesting project comes in. I love it when clients return over the years. And when my work is recognized by my peers and colleagues, I’m thrilled.

What are some of the accolades you’ve received over your career?

I’ve mastered over 100 Grammy-nominated records, over a dozen Grammy-winners, and I have personally won two Grammy Awards: for the Anthology of American Folk Music (with Charlie Pilzer, Jeff Place and Pete Reiniger) and Screamin’ and Hollerin’ the Blues: The Worlds of Charley Patton (with Matt Sandoski, Chris King, and Dean Blackwood.)

What are some of the professional associations you’re involved with?

I’ve been a member of AES (Audio Engineering Society) since 1975, and try to attend the annual conventions every year. Lately, the prime attraction is seeing fellow engineers, producers and equipment designers I’ve known over the years.

I’ve also had fun guest lecturing at UC Denver and UC Boulder, and participating in panels and workshops at industry conferences and events. This year Anna Frick and I will be on an AES panel discussing our work on Paramount Records box sets.

I joined NARAS (National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, the Grammy organization) as soon as I had the credits required for membership. This is my 30th year, and I’m serving my first term as a member of the San Francisco Chapter’s Board of Governors. I’d like to see all music makers join this vital organization.

Tell us about some of your hobbies and what you do for fun.

Besides music, I love to ride my bike. Boulder is a great town for biking, and one of my favorite rides is the stretch from Boulder to Lyons. Every year for Rockygrass I try and ride my bike there. I recently hung up my paragliding wing, but enjoyed that for many years. I’m a firefighter with the Boulder Mountain Fire Protection District’s volunteer department, and drive the big red trucks. Watch out, everyone.