If you’re a composer of contemporary classical music, your works will live on in perpetuity-on the web, at least. New York University is archiving the careers of hundreds of contemporary classical composers in a web-based project that is scalable and viable for the long term. It includes recorded music content and manuscripts. It doesn’t require permission or licensing from the subjects -though NYU is nice enough to ask permission.

I learned about NYU’s Archive of Contemporary Composers at February’s Music Library Association Conference in Denver.

Airshow works with music libraries, music archives and recorded music collectors through our Restoration Center. We’ve learned that digitally preserving and presenting music collections is a challenge for organizations that typically operate on small budgets focused on providing real-time services to patrons and scholars. The NYU project appealed to me as a tool for a scholar or collector to make a real contribution to the cultural record by aggregating available digital content when they cannot finance or get permissions to preserve and present analog material or content that is trapped in a dark archive. Aggregating existing web assets into a perpetual archive is a step to stop the loss of cultural content, even as scholars and collectors race against time to digitize fragile analog content or free up digital content that is captive to rights constraints.

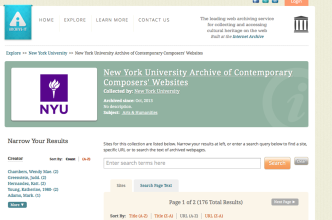

As described by Robin Preiss and Kent Underwood of NYU, the small team at NYU identified an initial group of a few hundred active composers of contemporary classical music, and administered a brief survey to determine the extent of their online presence and willingness t o have their websites archived. Then they created a collection at the Internet Archive using its Archive-It (AI) platform. The team recently added a visually attractive WordPress interface (that is still being developed) that links to the composers’ websites as indexed and stored by Archive-It, and to the composers’ sites on the live web.

o have their websites archived. Then they created a collection at the Internet Archive using its Archive-It (AI) platform. The team recently added a visually attractive WordPress interface (that is still being developed) that links to the composers’ websites as indexed and stored by Archive-It, and to the composers’ sites on the live web.

The Internet Archive is best known for the Wayback Machine, its perpetual archive of (nearly) all web content. While web pages have an average digital life of 45-75 days, the Wayback Machine regularly crawls the web and captures web pages for the long term record. The Wayback Machine is not particularly user friendly, but Archive-It, its companion, is. Archive-It works with over 300 collecting organizations including governments, nonprofits and schools for which the Archive-It presence is a small part, and with collecting organizations that exist solely to create and update an Archive-It collection.

I had just read Jill Lepore’s article in The New Yorker (Jan. 26), “The Cobweb,” where she visits the Internet Archive in its headquarters, a Greek Revival church in the Presidio in San Francisco, to meet with its founding visionary Brewster Kahle. Lepore’s example of the importance of the Archive is its capture of the short-lived web post by a Ukrainian separatist leader claiming to have downed the Maylasia Airlines flight over Donetsk. The post was easy to find because a scholar had recently submitted a list of Ukranian and Russian websites, the Ukraine Conflict collection, which the Archive aggregated via Archive-It. (Examples of collections capturing unique political moments are the Human Rights Documentation Initiative from the University of Texas and the International Whistleblower Archive, some of which could be used as examples by a California whistleblower attorney or other legal advisor.) Cultural collections include academic and nonprofit folk and folklore, classical music and sacred music among others.

The team at NYU submitted its curated list of composer websites (many of which contain recorded content and manuscripts) to the Internet Archive, which assembled the URLs into a directory. NYU was able to schedule regular automated captures of its collection of sites, and uses other curatorial tools of Archive-It.

Archive-It collections are continually updated as the Wayback Machine crawls the web and adds new versions of the web pages to collections. Thus, once set up, an Archive-It collection is self-sustaining and refreshed automatically. Collecting organizations can continue to submit new URLs to Archive-It as new sites come online or to modify a collection’s focus. Many artist websites include audio and video material hosted on the site, as well as links to third party media hosts like YouTube or Vimeo. Archive-It does not include the third party links, and does a spotty job, at present, of archiving the AV content of a site. NYU has a two-year grant to work with the Internet Archive to make this function more robust, yielding archived sites that more closely approximate sites on the live web.

Contemporary classical composers are going to be documented in great detail; a second collection, compiled by the Borrow Direct library consortium and including several dozen non-duplicated composers, is also hosted by Archive-It.

While viewing the NYU presentation, two easy-to-implement ideas came to mind:

• Collectors who have established some web presence for their unique collections can easily add value to-and expand the scope of-their efforts by curating a collection at Archive-It that includes the collector’s own site plus associated commercial or fan sites, reviews published online, or academic sites.

• Artists who enjoy being part of a creative community can document that community, the careers of its members, and their interactions and collaborations in perpetuity by giving it a name, an image and a home at Archive-It.

The Internet Archive holds regular live webinars to introduce potential collecting organizations to its methods. Check them out.

View the NYU team’s presentation, “Web Archiving for Music History.”

Thank you again to Diane Steinhaus, Susannah Cleveland and Laurie Sampsel for welcoming Airshow to the MLA conference.